by Bob Andelman

"I enjoyed the military. It was precise. It was teamwork. Maybe I like football for the same reason. Football is fairly macho; it brings out the macho in guys that other sports don't bring out. It was something we watched in Viet Nam when I was there. If we could get near a TV and football was on, we'd watch it."

Frank Bryant

Former Army helicopter pilot

Long Beach, California

Former Army helicopter pilot

Long Beach, California

The blitz.

The bomb.

Down in the trenches.

Aerial assault.

Field generals.

Quick strike.

If you haven't noticed how football is steeped in military terminology and strategy, you haven't been paying attention.

"Sports ought to be the substitute for war," Dr. William J. Beausay says. "When you listen to sportscasters and coaches, the war metaphors that they use to describe the game just go on and on. You could write a dictionary of the war metaphors that are used to describe athletic contests. That is not an accident. I think that the same genetic drive in the human being is being acted out and in this case it is sports instead of the battlefield."

Nobody promotes an NFL game by saying it's gonna be a party. They say, "It's gonna be a war!"

More proof:

Team names are almost all war-like: Vikings, Patriots, Chiefs, Seahawks, Buccaneers, Raiders, Chargers, Cowboys. Even the animals teams choose to represent are aggressive by nature: Rams, Falcons, Eagles, Bengals, Broncos, Lions, Bears.

The cities they represent? Ancient clans and tribes on missions to take and defend territory. They stand up for their community honor. They put forth a bruising, total effort.

Military games have a lot of appeal. They involve strategy and calculation: the manipulation of varied components to accomplish a common goal, outsmarting, outwitting, outplaying and outfighting an opponent. Your army exists to battle and win, to achieve its goal it fights both offensively and defensively. Football is a military game with military correlates. It appeals on that basis.

The game's war cry? "Take no prisoners." "No one here gets out alive."

After a Big 7 Conference game in Kansas City, Oklahoma coach Bud Wilkinson was seen reading a book about General Rommel and the fighting in North Africa during World War II. Questioned by sportswriter Volney Meece about his choice in reading material, Wilkinson said, "With the tanks and everything they were planning to outflank the enemy, to fool them about which direction they were going to go. Desert warfare is exactly like planning a football game."

Football represents the epitome of 19th century engineer Frederick Taylor's belief that the most efficient organization would be one where the workers don't make many decisions. To win in football you have to use the very same concepts: Division of labor, very rigid rules and regulations, highly scientific training procedures and, more than anything else, you have to rationalize. You have to eliminate anything that is ad hoc. It has to be 11 human beings working as a machine. The entire organization must be geared toward producing these highly efficient machines. Just like industry.

But Dr. Allen L. Sack, a Taylor proponent, wonders if football may be out of synch with late 20th century life.

"Taylor believed that the best organization would be more and more management with management making all the decisions, where the workers shut up and were compensated fairly with monetary rewards. They were not meant to think," Sack says. "But the newest movements in management thought emphasize employee involvement. Total quality management puts the emphasis on the workers who are closest to the action being involved and discussing how to improve and become more efficient. The Japanese mauled us because we were late in realizing this. IBM has had problems because of this -- centralization, lack of involvement of the work force. It seems the whole world is now discovering that maybe it's more efficient and effective to treat workers or athletes as valuable human resources whose ideas and opinions about running things should be taken into consideration.

"Maybe football is only a preparation for military life, for winning wars or going into the front lines," Sack says. "Maybe it's no longer the best preparation for a life in a modern corporation where you have to be able to listen and to take the lower echelon's opinion into consideration."

The current coaching philosophy of football and some other sports came out of World War II and the Korean War. Many coaches are products of those wars. They believe the best approach to winning in football is the same as winning in the military and that proves true in most cases.

Are military skills and the way we look at the world psychologically the best tools for performance and success in a modern approach to industrial society? As another generation passes without being sent to a full-scale, multinational war, Sack suggests football will become more important as a military-style outlet.

"It's necessary that we have that kind of exposure because it's a reality that there are times when people do fight to the death," he says. "In those times you probably don't need democratic institutions. It's not like you take a vote (to go to war). There are places where the most effective organizational tools are probably Tayloristic principles and the football approach. But I think there are fewer and fewer areas of regular life where that really fits."

* * *

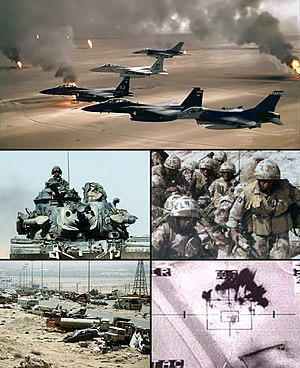

Teamwork is another way football parallels the military. Without teamwork, the 49ers and Cowboys are lost. Without its multinational allies, Operation Desert Storm would have been a disaster for the U.S. armed forces.

Teamwork is the essence of football.

Young men learn the value of teamwork through football. How to work together. On a great football team you can see that and appreciate it.

"Baseball is an individual game," says Pat Harmon, historian of the College Football Hall of Fame at Kings Island amusement park near Cincinnati. "The batter is there and what he does, he does himself. Football is a team game. You have to have the performance of all the people on the team to make a team successful."

We use the example of "pulling together as a team," "conquering our problems as a team" and "only together can we win." If everyone does their specific task then goals will be accomplished. That fits with bureaucracies, too. Football is a rigidly timed game and we are a time-oriented society.

We each have a certain role and to the extent that all of us can do our roles well and we mesh and complement one another, we will be successful in life as in football. "That part hits home for me," Dr. Rick Weinberg says, "and in fact in my work with groups very often I use the metaphor of a professional sports team as a way to build a sense of teamwork."

Teamwork is instilled in children from the earliest days of their education. It's a concept that we very much want to teach our kids. The whole idea of teamwork at that level of development is very useful to get kids involved in sports and watching sports and participating in sports as a way of on-line learning about the value of teamwork. Once you have that as a kid it stays with you as a meaningful adult value.

But the concept of the team runs smack into the treasured American spirit of individualism and individual achievement, doesn't it?

"It is a contradiction, I think," Sack says. "On the one hand, as Americans, we like to think that these are individuals who are succeeding on their own individual efforts. We love heroes. We are a hero-oriented society. We value individualists, so we delude ourselves into thinking that a football team is 11 individuals."

Nothing could be further from the truth. There is no game in the United States where the individual is more subservient to the group.

"When I think of football, I think of a pinball machine," Sack says. "The little receivers are running back and forth and the ball is going up and down and being hit; football players are like the little arms that are flicking and there is a coach in back of all that who is pushing the buttons. There is all kinds of action, lights flashing and there's ringers and buzzers. The players themselves are like little parts within the pinball machine. Every one of their movements is perfectly planned and timed. They are being dominated and synchronized and told exactly what to do at certain moments.

"What is it that we like about watching that?" Sack asks. "We like to watch the quarterback, the hero, because it gives us empathy in terms of individualism. Do we identify with the tackles and the guards in the same way? Probably not. I think we are probably most amazed by the tremendous coordination of all this working together."

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=c50cc354-3809-4e46-8c02-333f9b169b69)

No comments:

Post a Comment