by Bob Andelman

"At the height of the game, if a player is injured -- I hate to admit it -- but my first thought is, 'Goddammit, we're going to waste five minutes while they take this guy off the field!' "

Jim Melvin

Newspaper editor

St. Petersburg, Florida

Newspaper editor

St. Petersburg, Florida

The only guys who don't get some cheap thrill out of the violent nature of football are the ones who don't watch it. For most men -- the same guys who clench their own fists during a boxing match and bob and weave in their seats -- a cathartic release occurs by watching a defensive back as he snares a wide receiver in mid-air and slams him back down to earth.

• "I like contact sports," Buffalo fan Ralph Weisbeck says. "I'm built light and was never good at sports but I like the bit of mayhem you see on a Sunday afternoon."

Snap!

• "The violence is a part of the game," financial accountant Larry Selvin says. "It's a brutal, vicious sport. But fans aren't bothered by it."

Crackle!

• "It's just human nature that we go to a hockey match and we want to see blood and guts and fights," Volney Meece says. "It's a Catch-22 thing. I think the average fan wants to see a helluva hit. You see those highlight films on ESPN and on the networks, the great shots where a guy gets cartwheeled up in the air and slammed into the turf. Or when somebody breaks their leg like Joe Theisman did and the bone was sticking out at a 45-degree angle. They show that over and over."

Pop!

• "I hesitate to say the violence is why I watch," Louisville Courier-Journal copy chief Jim Luttrell says. "Maybe the raw power of the game. The grunting. I get a kick out of watching NFL films with the sound of the hits."

As hard to swallow as those comments may be for some people, experts acknowledge that violence is exactly why men love football.

"Sports have been around since the caves, or at least at that part of man's evolution when he started to increasingly sublimate his aggressive drive, to channel his pride in a productive way," Dr. Mark Unterberg says. "It may have started out as preparatory for the hunt or defense or a play-type situation for acting out what would be the real thing later on. For example, lacrosse is a definite offshoot of an Indian game that tribes would play with each other instead of going to battle."

Unterberg says the Indian sport, like lacrosse, could turn bloody. Do fans really want blood?

"No. It's a metaphor," Unterberg says. "At some level it gratifies the need for that. Maybe the ultimate demise of the opponent. Conquering the adversary."

"No. It's a metaphor," Unterberg says. "At some level it gratifies the need for that. Maybe the ultimate demise of the opponent. Conquering the adversary."

We want violence. In conscious and unconscious ways, it makes us feel more alive to see some stranger on a football field get trashed. The sounds of crashing pads, of bones popping. But that's the short-term view. As soon as the blood-lust is satisfied, we want the victim to come to his feet and hobble off the field to a round of polite applause.

"You know the truth? It's a violent game. And I'm not a violent guy. But I am a trial lawyer. By nature, I'm a competitive guy. I played sports all my life," attorney Peter Hendricks says.

It doesn't have to be football. Driven by a good car crash lately? You can't go past a wreck without looking. "Oh, how horrible," but hmmm, were there any bodies? Anybody badly mangled?

"That's an Aristotelian paradox I don't quite understand," says Dr. Daniel Begel, a Milwaukee psychiatrist and founder of the International Society for Sports Psychiatry. "All I know is that when we try to organize a game among football coaches, ex-players and team doctors, we have a real hard time getting more than 12 people for a game once or twice a year. It's practically impossible -- and these are people who love football. Football coaches at the college level, for recreation, do not play football. They play basketball, handball or racquetball."

Even so, Begel doesn't think football is a violent game.

"It may be harder for people to control themselves in a football game than in a basketball game," he says. "It's a great pleasure to play a football game in which people are just enjoying the game and loving the competition. But recreational football seems to slip very easily into displays of aggression. It may be uncomfortable for people. People may not be able to handle it, but I do not think violence is intrinsic to the game. I think football is aggressive, but played fairly. I'm not sure -- well, I guess it is violent if there is contact. I think of violence as doing harm to people. I don't think there is anything harmful about a good tackle."

And there's nothing wrong with wanting to watch a good, clean tackle being made, either.

"There is a mistaken notion held by a lot of people in football that it is such a violent game," Begel says. "I think of violence as harmful activity. I think of violence as the person who is cutting someone off at the knees to try to injure them. I think of violence as someone like the defensive back who builds his reputation as a big hitter but is always just a little bit late. I think of that as a violent person. I do not think of the great linebacker who is all over the field and makes crushing tackles as necessarily a violent person. A strong and an aggressive person and a competitive person but not necessarily violent. It may just be a semantic distinction. That's not to say that the fan isn't looking for violence. I think that if the main motivation was the thirst for violence they would all be at hockey games."

There are 22 positions on an NFL football field. Some require skill, some containment, some -- like quarterback -- require leadership. Some positions are just aggressive death-and-mayhem positions like defensive linemen and linebackers.

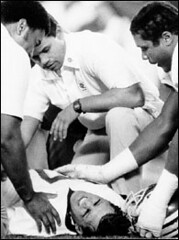

"I think as people watch the game they'll be critical or applauding the aggressiveness or violence or enthusiasm of the player depending on what they think is required or whether he is getting the job done or not," Dr. Gregory B. Collins says. "Most people, if they played the game, have been knocked around so they know what it's like. They know how to dish it out and they know how it feels to be on the receiving end. I think there is identification both ways. When the player is knocked out cold on the field, people clap when he gets up. On the other hand, if it's a heckuva hit, people clap when he goes down. There is identification on both sides of that issue."

No one sitting in Veterans Stadium or in his living room in New Orleans wants to see Saints quarterback Steve Walsh get seriously hurt by a bad hit. But there is an undeniable thrill that runs up and down the spine when a Reggie White breaks through the line and puts Walsh flat on his ass.

"Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!"

Only Walsh, his offensive line and the coaches are crying, "No! No! No!"

What's so appealing about that? Fans of any age and size can vicariously play the game through the Monsters of the Midway without getting themselves beaten black and blue. "The violence is attractive," Shawn Cahill says. "When you see the highlights or bloopers, it's usually a big hit."

What's so appealing about that? Fans of any age and size can vicariously play the game through the Monsters of the Midway without getting themselves beaten black and blue. "The violence is attractive," Shawn Cahill says. "When you see the highlights or bloopers, it's usually a big hit."

Is this attachment to vicarious violence healthy?

"I don't think there is any harm in it," Dr. Robert B. Cialdini says, "especially if it lets off certain kinds of steam that modern society doesn't typically let men find outlets for their physical energies."

The United States is a very competitive society, Cialdini says, possibly the most violent society of all of the major industrialized nations. Football fits easily into such a place where young males are socialized and raised with the expectation of being powerful and aggressive.

"It is an aggressive sport," says Dr. D. Stanley Eitzen, a psychology professor at Colorado State University and co-author (with Dr. George H. Sage) of Sociology of North American Sport (Wm. C. Brown). Eitzen is also a past-president of the North American Society for the Sociology of Sports. "It is where you hit people. You move people. More than any other sport, boys play football. They have participated in it and it's kind of a male masculinity rite to play football and be tough and act like you like being tough even though you may not. To brag about hitting. I played football too and I can remember people saying, 'I can't wait until we start hitting in scrimmage.' The whole coaching fraternity asks us to be hitters and to deliver a blow. We are an aggressive society."

Men like to feel in control. That can be achieved not only by personal performance and personal accomplishments but to a significant degree by vicarious experiences. It's this vicarious experience that a lot of spectators need.

"There is data that has shown that people, depending on how much stress and tension they feel in their work, do the opposite in their release activities," says Dr. Seppo E. Iso-Ahola, a University of Maryland professor of sport psychology. "If you do the type of work that doesn't cause stress and tension, you will seek that in your leisure. If your work is too stressful, you want a tranquil, quiet and peaceful leisure type of activity."

Football provides an excellent opportunity for balancing these needs and the need for stress in a socially acceptable way. Pleasant stress. There is pleasant stress that is controllable by the person engaged in it. The heart rate of spectators goes up significantly during football games, more than other events. That shows that they are drawn not only by vicarious stresses and experiences but also by real stress of participation in the crowds.

"Everybody gets into it," Iso-Ahola says. "In Europe, what people value and appreciate is the skill. But in America that is less important than the fighting aspect. It supports the idea that American males love violence in sports.

"I suppose some people would say it goes all the way back to gunslinging and the Wild West syndrome," he says. "But you are really stretching explanations if you go that far in modern times. I don't think that anybody would be able to present any arguments that there is something genetically different about American men. There is not any data to support that, so therefore what you have left is the social environment in which we are living. We get exposed to maybe more violent models than they do in other cultures. That may be part of it."

* * *

American sports evolved in the early 1900s from a participation activity to a major form of entertainment, setting them apart from sports in other industrialized countries. Dr. Jay Coakley, a professor of sociology and director of the Center for the Study of Sport and Leisure at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, is the author of Sports in Society: Issues and Controversies (Moseby-Yearbook). He says that sports in England, for example, were always emphasized as participatory activities rather than entertainment or spectator activities.

"In England," Coakley says, "when sports emerged in the old private schools, there was a sense that the games were so important from a participant perspective that nobody should be excluded. If a sport was worth playing it was worth playing even badly because it was important for the people who participated. In the United States, we believe that if a sport is worth playing it is worth playing well and, in fact, trying to be the absolute best at it."

Coakley himself went to college on an athletic scholarship. He notes that Great Britain continues to emphasize participation while the United States leans toward an elitist participation of only the best playing sports in high school and college. A British college might have seven soccer teams. "You can say you play on the sixth side. Games were arranged between your sixth side and the sixth side from some other school," Coakley says. "The whole notion of one football team representing a university of 50,000 students is completely inconsistent with how the British look at intercollegiate sports."

There are other subtle cultural differences among industrial societies that lead sports to take different forms. Because sports are defined as a form of entertainment in American culture, we present them unlike any other culture. Some cultures want to emulate the commercialism of our sports but it scares the hell out of others because they think it is going to destroy the "purity" of their sports.

* * *

Isn't there something seriously missing in the lives of men who need to experience such violence?

Probably.

The second-hand pleasure we get when we witness any physical event, even within the context of a movie, satisfies a deep-seeded need. For whatever reason, as long as civilization has been around, men have been interested in the whole experience of being spectators, whether it's theater or athletics or some other art form. Men enjoy being fans as much as they enjoy being participants.

Dr. Daniel M. Glick describes a pent-up need in the psyche of contemporary American men. "A lot of men I see in my practice and that I know in the community are very, very frustrated. I think sports and athletics sometimes offer a vicarious vent for their own frustrated hostility and aggression," he says. "I think there is something primal and something cathartic in it. In all types of various cultures there have been spectator sports where there have been battles between individuals or groups in the name of sport and sometimes the stakes of the game literally meant life and death. That is a phenomenon that existed long before anybody even discovered football. There is something in the psyche, something primal, where people enjoy the spectator aspect of seeing people in battle."

Is violence good for the system? Is it bad? The answer might depend on whether you talk to a physician treating an injury, a psychologist or a sociologist. Then there are the specific issues of behavior modification, pleasure and pain, punishment and reward. When your team wins, it is a reward and so you modify your behavior and identification to reflect that.

"The deal is, kill the other team," Volney Meece says. "But I don't think they mean kill. They mean good hits."

Part of the sting of seeing men bash each other for three hours at a time on the gridiron is cushioned by the sight of their big, beefy frames insulated by pounds of padding.

"I'm not a big fan of the violence," Bill Evans says. "It's a violent sport but it doesn't seem that many people get hurt."

"I'm not a big fan of the violence," Bill Evans says. "It's a violent sport but it doesn't seem that many people get hurt."

Padding and helmets keep the action from appearing too painful to the casual viewer. So do rules intended to protect the quarterback from late hits. And when someone does get hit hard -- the crowd, after all, cries for blood -- fans come to their feet and snort their approval like wild beasts.

"A pro football player said to me once, 'Football is not a contact sport. it is a collision sport,' " Glick says. "It's crazy. When those guys get out there to play they are taking some major risks. A colleague who works with disabled people told me that the average pro football player comes out of professional football after a very brief career and most of them carry a 30 percent physical disability from knees or backs or elbows or shoulders or whatever. They don't walk away from football unscathed."

But for the fan, there is an allure of collision sports that has to do with power, control and dominance.

You know your boss is being manipulative. You know a person at your work place is trying to be dominant toward you. But these things are oftentimes very subtle and veiled. One thing that people are attracted to sports is that the play is right there in front of them. It's not disguised in doublespeak or technobabble. A power struggle takes place on the field and the players understand that the moment they step out on to the turf. It's going to be brought forth with much more clarity than in virtually any other social setting because there aren't that many situations in which we allow contact and physical collisions in which two individuals or two groups are competing for some goal.

* * *

If you sell widgets for 60 hours a week it takes a lot of pride and energy out of you. All of us, to some extent, are cogs in the occupational/professional hierarchy. For some men, watching football is a way to vicariously experience physical empowerment.

We don't have to be the one hitting the other guy but we can really feel good about watching our hero and cheering him on for making a great tackle or a great block. Boxing is probably an even more extreme identification with violence. "Punch that guy! Get him! Knock him on his ass!" It's what we'd like to do to a boss or an enemy. The feeling is that we are, in a limited way, satisfying our own need through this figure we're watching on the tube.

The football field -- and the stands around it, to a certain degree -- are places where men are allowed, even encouraged, to act out their aggressions. It's a setting in which the contestants have agreed to allow certain actions to take place that are forbidden in any other social setting. There is nothing like football in this way. Duplicate what the defensive lineman did on the field to a complete stranger in the parking lot after the game and it's illegal. If you try to get out of the boss' office and he tackles you to the floor, you are going to charge him with assault.

"A lot of times we have to restrain these actions," says Dr. John M. Silva, a University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill sport psychologist. (Silva once played tight end for the University of Connecticut Huskies.) "In collision sports there is a lot of release of restraint. Sometimes you might want to do something physical but you cannot do that. We're socialized in a civilized society most of the time to restrain those actions and sport allows us to exhibit some of those, within control."

Most experts argue that football provides a healthy catharsis to most men and even some women. Go ahead, scream, yell, jump up and down. Blow off steam. It's good medicine.

But football does not provide any psychological solution to the cause of your physical tension. You are still going back to your job on Monday morning, and if your boss was manipulative at 5 p.m., Friday, he or she will still be a manipulative bastard or bitch when you return.

Football fans fall into a cycle where tensions build all week. Football allows us to blow off steam for a few hours, but a day later the pot is whistling again. We haven't changed the actual source of our tension so the dynamics repeat.

"It is a sad commentary," Silva says. "Football is almost like an opiate for the masses. That is why a lot of people just can't wait till Wednesday -- Hump Day. One or two more days and they live for the weekend to get their little drug, their little release, and then they go back into the work place. They haven't really developed any better skills for dealing with their communication problems and the conflicts that exist at work."

In this way, Silva sees television as a cheap drug. Men think watching football makes them feel better because it provides a little release, but it may not necessarily be time well-invested.

In this way, Silva sees television as a cheap drug. Men think watching football makes them feel better because it provides a little release, but it may not necessarily be time well-invested.

Football is a distraction, Silva says, not a solution.

Through catharsis, men feel relief if they watch people hit each other. But an opposing theory suggests that seeing violent acts exacerbates a man's need to see or commit violence. At the end of the game we are even more hyped to clobber somebody. Sometimes it occurs because a guy's team wins, rather than loses. Need an example? How about the January 1993 riots in downtown Dallas that greeted the Super Bowl champion Cowboys? Fans were so worked up they overturned cars and broke through storefronts to vent their glee. The same thing happened a few months later in Montreal when the Canadiens won the NHL Stanley Cup, and in Chicago after that, when the Bulls won their third straight NBA championship.

"Aggression begets aggression," Dr. Bruce C. Ogilvie says. "There isn't a spilling away or draining away. What there is, is a laying of groundwork or bedrock to the aggressive or angry man. It certainly frees him from the basic human being that he is. He is an inadequate, insecure asshole. They can 'act out' this way but it doesn't translate into any constructive use of self-assertion in real life."

Do we really have a need to watch people hit each other?

"TV depicts violence -- the number of people that get in car wrecks, punching people out, the physical atrocities. Gangs are shooting at one another. If you watch the news you really are talking about reality," Dr. Thomas A. Tutko says. "They dictate the violence. Sport reflects what goes on out there.Whether sport promotes it is another question. It's the chicken and egg routine, and I'm not sure which caused which."

No comments:

Post a Comment